Section 2.4 Green's theorem in the plane

Subsection 2.4.1 Tangential form of Green's theorem and curl

Theorem 2.4.1. Green's theorem (circulation or tangential form).

Let \(\mathcal{C}\subseteq\R^2\) be a piecewise smooth simple curve with positive (counterclockwise) orientation, and let \(\mathcal{R}\subseteq \R^2\) be the region it encloses. If the component functions of \(\boldF=\angvec{F_1, F_2}\) have continuous first-order partial derivatives on an open set containing \(\mathcal{R}\text{,}\) then

Example 2.4.2. Circulation around semicircle.

Use Green's theorem to Compute \(\oint_\mathcal{C}\boldF\cdot d\boldr\text{,}\) where \(\boldF=\angvec{y^2, 3xy}\) and \(\mathcal{C}\) is the simple positively oriented curve obtained by joining the line segment from \((-1,0)\) to \((1,0)\) the the upper half of the circle \(x^2+y^2=1\text{.}\)

Letting \(\boldF=\angvec{F_1, F_2}\text{.}\) The curve \(\mathcal{C}\) bounds the region

Since \(\mathcal{C}\) is oriented counterclockwise, we apply Green's theorem to conclude

Definition 2.4.3. Scalar curl.

Assume the component functions of the vector field \(\boldF=\angvec{F_1, F_2}\) have first-order partial derivatives on a domain \(D\text{.}\) The scalar curl (or \(k\) component of curl or circulation density) of \(\boldF\text{,}\) denoted \((\curl \boldF)\cdot \boldk\text{,}\) is defined as

The vector field is irrotational on the domain \(D\) if

for all \((x,y)\in D\text{.}\)

Corollary 2.4.4. Area via line integral.

Let \(\mathcal{C}\subseteq\R^2\) be a piecewise smooth simple curve with positive (counterclockwise) orientation, and let \(\mathcal{R}\subseteq \R^2\) be the region it encloses. If the component functions of \(\boldF=\angvec{F_1, F_2}\) have continuous first-order partial derivatives on an open set containing \(\mathcal{R}\text{,}\) and if \(\boldF\) satisfies

then

A typical example of such a vector field is \(\boldF=\frac{1}{2}\angvec{-y,x}\text{.}\)

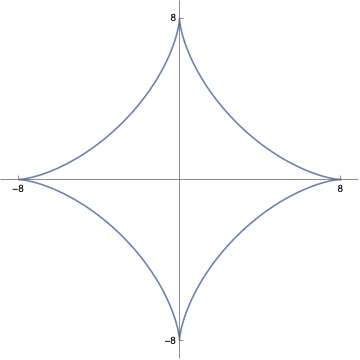

Example 2.4.5. Area of astroid.

Use Corollary 2.4.4 to compute the area of the astroid curve \(\mathcal{C}\colon x^{2/3}+y^{2/3}=4\) with parametrization \(\boldr(t)=\angvec{8\cos^3 t,8\sin^3 t}\text{,}\) \(0\leq t\leq 2\pi\text{.}\)

Evaluating \(\boldr(t)\) at \(t=0\) and \(t=\pi/2\text{,}\) we see that \(\boldr(t)\) traverses \(\mathcal{C}\) in the counterclockwise direction. While we're at it, we compute:

Applying Theorem 2.4.1 to the vector field \(\boldF=\angvec{0,x}\text{,}\) which satisfies \(\curl\boldF\cdot \boldk=1\text{,}\) we compute

Theorem 2.4.6. Scalar curl interpretation.

If the component functions of \(\boldF=\angvec{F_1, F_2}\) have continuous first-order partial derivatives on an open set containing the point \(P=(x,y)\text{,}\) then

where \(C_R\) is the simple positively oriented circle of radius \(R\) centered at \(P\text{.}\)

Proof.

See proof of the more general result Theorem 2.7.9 .

Remark 2.4.7. Scalar curl interpretation.

From the limit expression (2.4.2) we extract the valuable approximation formula

This can be understood as saying that the scalar component of curl at a point \(P=(x,y)\) is approximated by the circulation density quantity

whose units are of the form unit circulation per unit area. This gives us a more concrete understanding curl as a measure of the fluid's tendency to rotate about a given \(P\text{.}\) In particular if the fluid is assumed to be irrotational (\(\partial F_2/\partial x-\partial F_1/y=0\)), this means that the region contains no vortices, points about which the fluid rotates like a whirlpool.

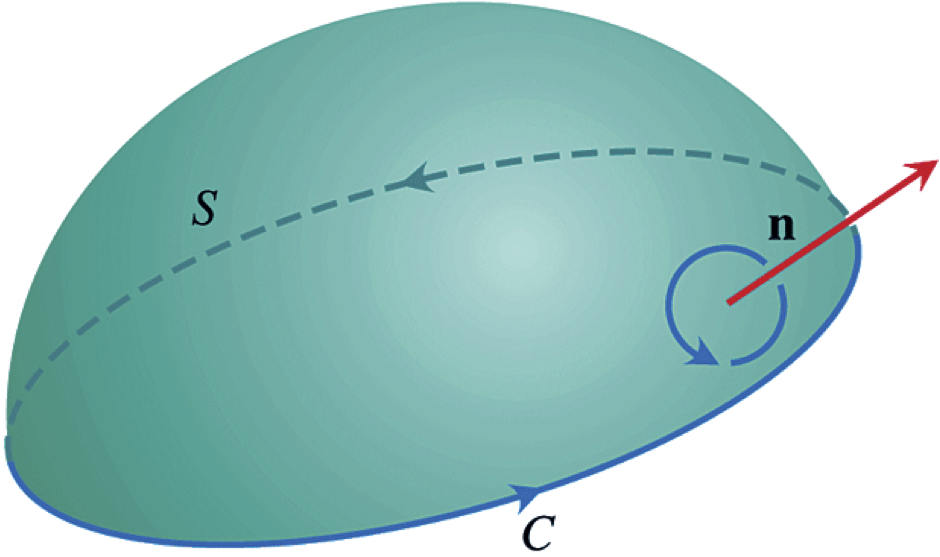

Subsection 2.4.2 Normal form of Green's theorem and divergence

Corollary 2.4.8. Green's theorem (flux or normal form).

Let \(\mathcal{C}\subseteq\R^2\) be a piecewise smooth simple curve with positive (counterclockwise) orientation, and let \(\mathcal{R}\subseteq \R^2\) be the region it encloses. If the component functions of \(\boldF=\angvec{F_1, F_2}\) have continuous first-order partial derivatives on an open set containing \(\mathcal{R}\text{,}\) then

Here \(\boldn\) is understood to be the outward unit normal vector to \(\mathcal{C}\text{.}\)

Definition 2.4.9. Divergence.

Assume the component functions of the vector field \(\boldF=\angvec{F_1, F_2,\dots, F_n}\) have first-order partial derivatives on a domain \(D\subseteq \R^n\text{.}\) The divergence of \(\boldF\text{,}\) denoted \(\diver \boldF\) or \(\nabla\cdot \boldF\text{,}\) is defined as

The vector field is incompressible on the domain \(D\) if

for all \(((x_1,x_2,\dots, x_n)\in D\text{.}\)

Example 2.4.10. Flux across square.

Compute the outward flux of \(\boldF(x,y)=\angvec{2e^{xy},y^3}\) across the square bounded by the lines \(x=\pm 1\text{,}\) \(y=\pm 1\text{.}\)

Let \(\mathcal{R}=[-1,1]\times [-1,1]\) be the given square region, and let \(\mathcal{C}\) be the perimeter of \(\mathcal{R}\text{,}\) oriented counterclockwise. By Corollary 2.4.8, we have

Theorem 2.4.11. Divergence interpretation.

If the component functions of \(\boldF=\angvec{F_1, F_2}\) have continuous first-order partial derivatives on an open set containing the point \(P=(x,y)\text{,}\) then

where \(C_R\) is the simple positively oriented circle of radius \(R\) centered at \(P\text{,}\) and \(\boldn\) is the unit outward normal vector to \(C_R\text{.}\)

Proof.

See proof of the more general result Theorem 2.8.10.

Remark 2.4.12. Divergence interpretation.

From the limit expression (2.4.4) we extract the valuable approximation formula

This can be understood as saying that the divergence of \(\boldF\) at a point \(P=(x,y)\) is approximated by the flux quantity

whose units are of the form unit flux per unit area. This allows us to understand the divergence at \(P\) to be a measure of how the fluid flows out from or in toward \(P\text{.}\) Even more concretely, if \(\nabla \cdot \boldF(x,y)=0\) for all \((x,y)\text{,}\) then it follows from Corollary 2.4.8 that the flux through any closed curve around \(P=(x,y)=0\text{.}\) Thus a fluid's being incompressible (\(\nabla\cdot \boldF=0\)) means that whatever amount of fluid enters a given enclosed region is equal to the amount that leaves it. In fluid dynamics this is sometimes described as there being no sources or sinks in the region.

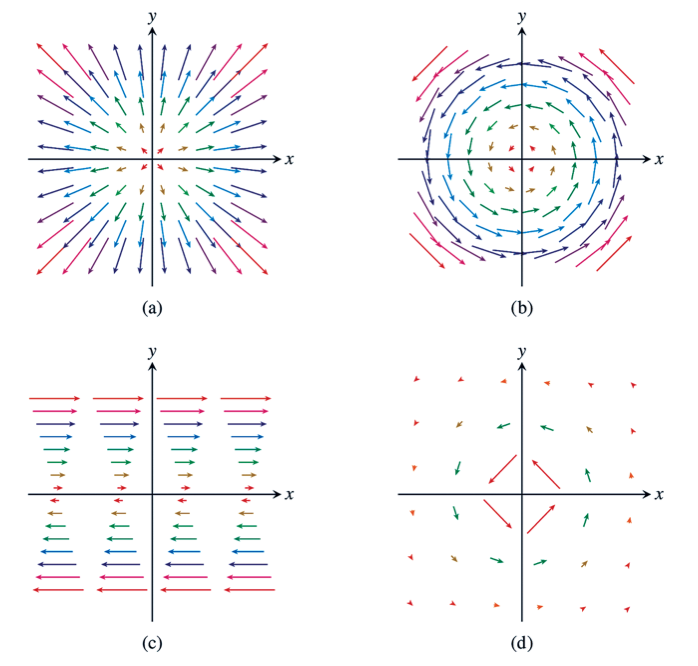

Example 2.4.13. Visualizing curl and divergence.

The vector field diagram is provided for each \(\boldF\) below. Using our interpretations of curl and divergence, try your best to visually identify points \(P\) where \((\curl F)\cdot\boldk(P)=0\) and/or \(\nabla\cdot \boldF(P)=0\text{.}\) Confirm your answers by computing \((\curl F)\cdot\boldk\) and \(\nabla\cdot \boldF\) algebraically. Assume \(c\) is a nonzero fixed constant.

-

Uniform expansion/compression.

\(\displaystyle \boldF(x,y)=\angvec{cx, cy}\)

-

Uniform rotation.

\(\displaystyle \boldF(x,y)=\angvec{-cy, cx}\)

-

Shearing flow.

\(\displaystyle \boldF(x,y)=\angvec{cy, 0}\)

-

Whirlpool.

\(\displaystyle \boldF(x,y)=\frac{1}{x^2+y^2}\angvec{-y, x}\)

-

Algebraically, we have \(\curl\boldF\cdot \boldk=0\) and \(\diver \boldF=2c\text{.}\) Can we see this in the diagram?

Curl. Put a pinwheel down in the first quadrant. By symmetry about the line connecting the origin to the center of the pinwheel, we see that what ever counterclockwise push there is on the lower right section of the pinwheel is matched by a symmetric clockwise push on the upper left. Thus total circulation around any small circle is zero, making flux zero. The same argument applies to any quadrant.

Divergence. We can at least estimate a positive divergence using flux across a small circle. Place a little circle somewhere in the first quadrant. Since the inward arrows at the bottom left of the dist are beaten out by larger outward arrows at the upper left of the circle, net flux out is positive.

-

Algebraically, we have \(\curl\boldF\cdot \boldk=2c\) and \(\diver \boldF=0\text{.}\) Can we see this in the diagram?

Curl. We can at least estimate a positive curl using circulation of the pinwheel. Again, place the pinwheel anywhere in the first quadrant. The coutnerclockwise push from the arrows at the upper right beat the clockwise push from the arrows at the lower left, giving this a positive circulation. Since flux at a point \(P\) can be estimated by the circulation around a small circle at \(P\text{,}\) we can estimate that the flux at any point \(P\) is positive.

Divergence. Now place a little disk down somewhere. It is clear by the symmetry about the line from the origin to the center of the disk that for each inward arrow there is a matching outward one, flux across the circle zero.

-

Algebraically, we have \(\curl\boldF\cdot \boldk=-c\) and \(\diver \boldF=0\text{.}\) Can we see this in the diagram?

Curl. We can at least estimate a negative curl at each point in the plane, by looking at the circulation of a little pinwheel. Placing a pinwheel in the first quadrant, for example, we see that the clockwise push at the top beats out the counterclockwise push at the bottom, resulting in a negative circulation.

Divergence. This we can see. For any disk placed in the upper half of the plane, for each arrow in at the left of the disk there is an equal arrow out of the disk directly to the right.

Algebraically, we have \(\curl\boldF\cdot \boldk=0\) and \(\diver \boldF=0\text{.}\) Can we see this in the diagram? A by now familiar argument easily convinces us that flux across any circle (not centered at the origin) is zero, and hence that divergence is zero everywhere. The fact that curl is zero is harder to see. Indeed, the vector field is very similar in nature to (b), where the scalar curl is positive. This indicates the limitations of our ability to “see” curl in a vector field diagram!