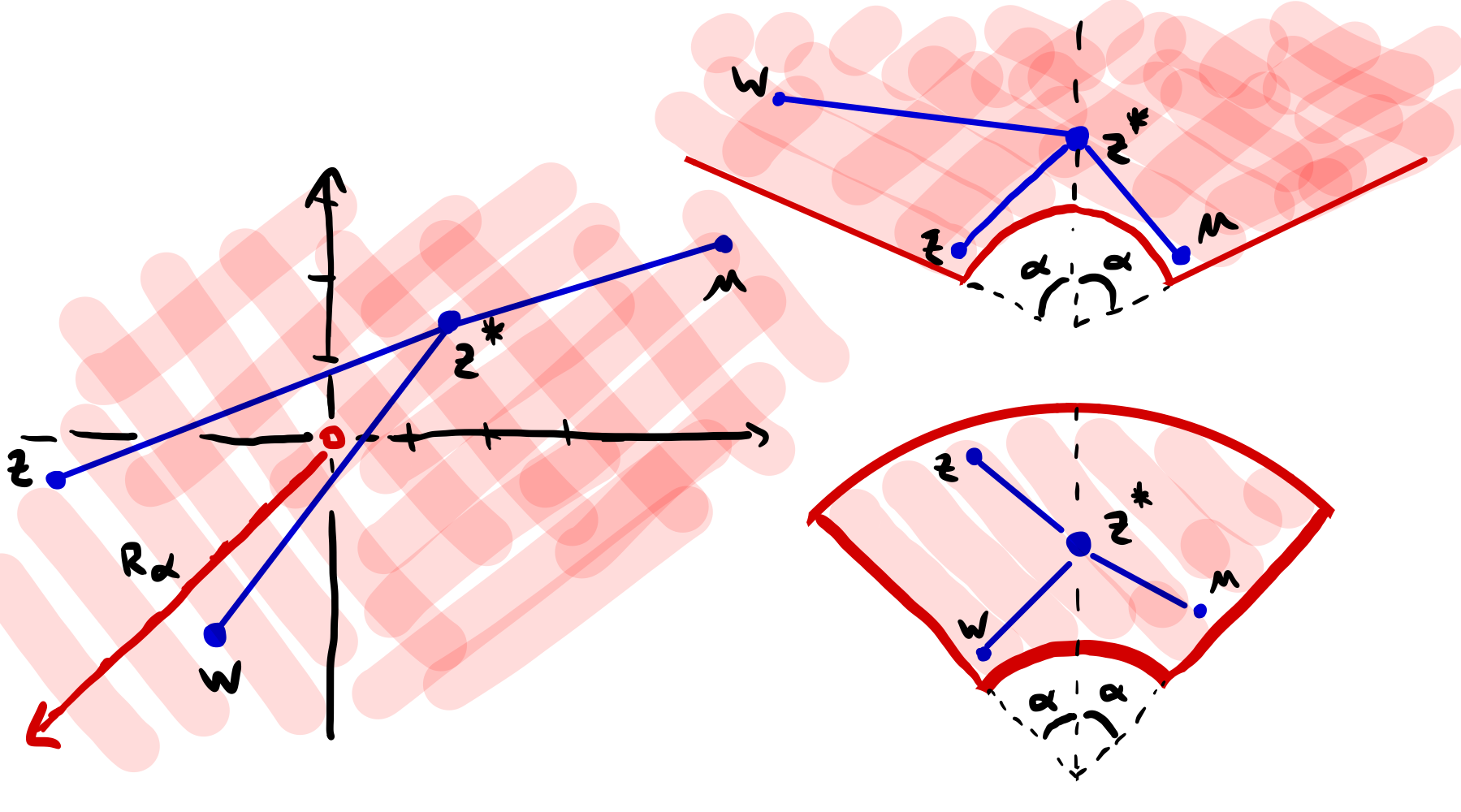

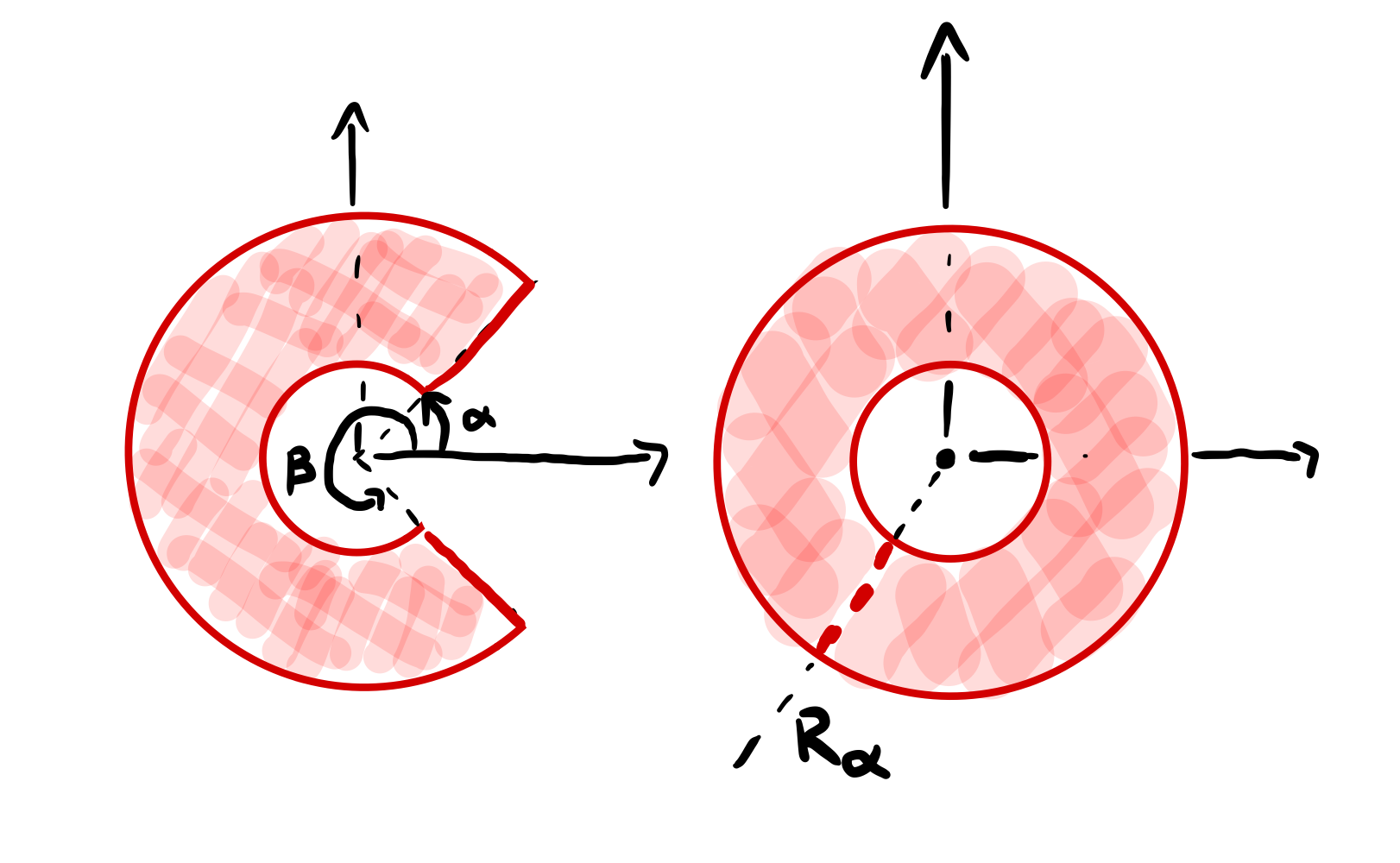

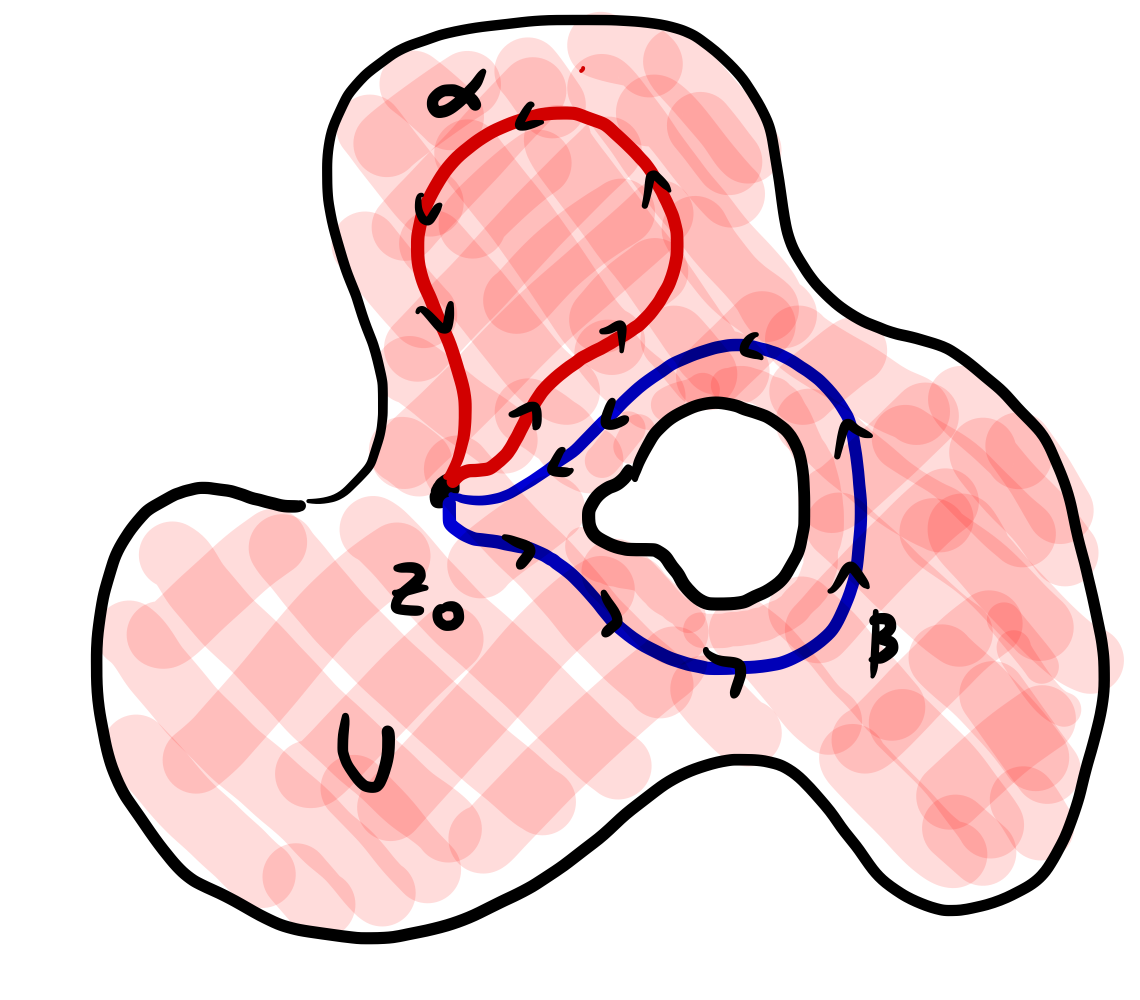

Pick any element \(z^*\in U\text{.}\) Since \(U\) is open and connected, it is polygonally connected. Thus for any \(z\in U\) there exists a polygonal path beginning at \(z^*\) and ending at \(z\text{.}\) We define the function \(F\colon U\rightarrow \C\) as

\begin{equation}

F(z)=\int_{z^*}^z f\, dz\text{,}\tag{1.54}

\end{equation}

where \(\int_{z^*}^z f\, dz\) denotes the contour integral along any polygonal path from \(z^*\) to \(z\text{.}\) Since we assume that line integrals of \(f\) are path independent, our function \(F\) is well-defined: i.e., \(F(z)\) does indeed return a single well-defined value, no matter which path you choose. It remains to show that \(F\) is an antiderivative of \(f\) on \(U\text{.}\)

Pick any \(z_0\in U\text{.}\) Firstly, since \(U\) is open we can find a \(\delta> 0\) such that \(B_{\delta}(z_0)\subseteq U\text{.}\) We will prove that \(F'(z_0)\) by showing that

\begin{equation*}

F(z)-F(z_0)=f(z_0)(z-z_0)+r(z)

\end{equation*}

for all \(z\in B_{\delta}(z_0)\text{,}\) where \(r(z)\) satisfies

\begin{equation*}

\lim\limits_{z\to z_0}\frac{\abs{r(z)}}{\abs{z-z_0}}=0\text{.}

\end{equation*}

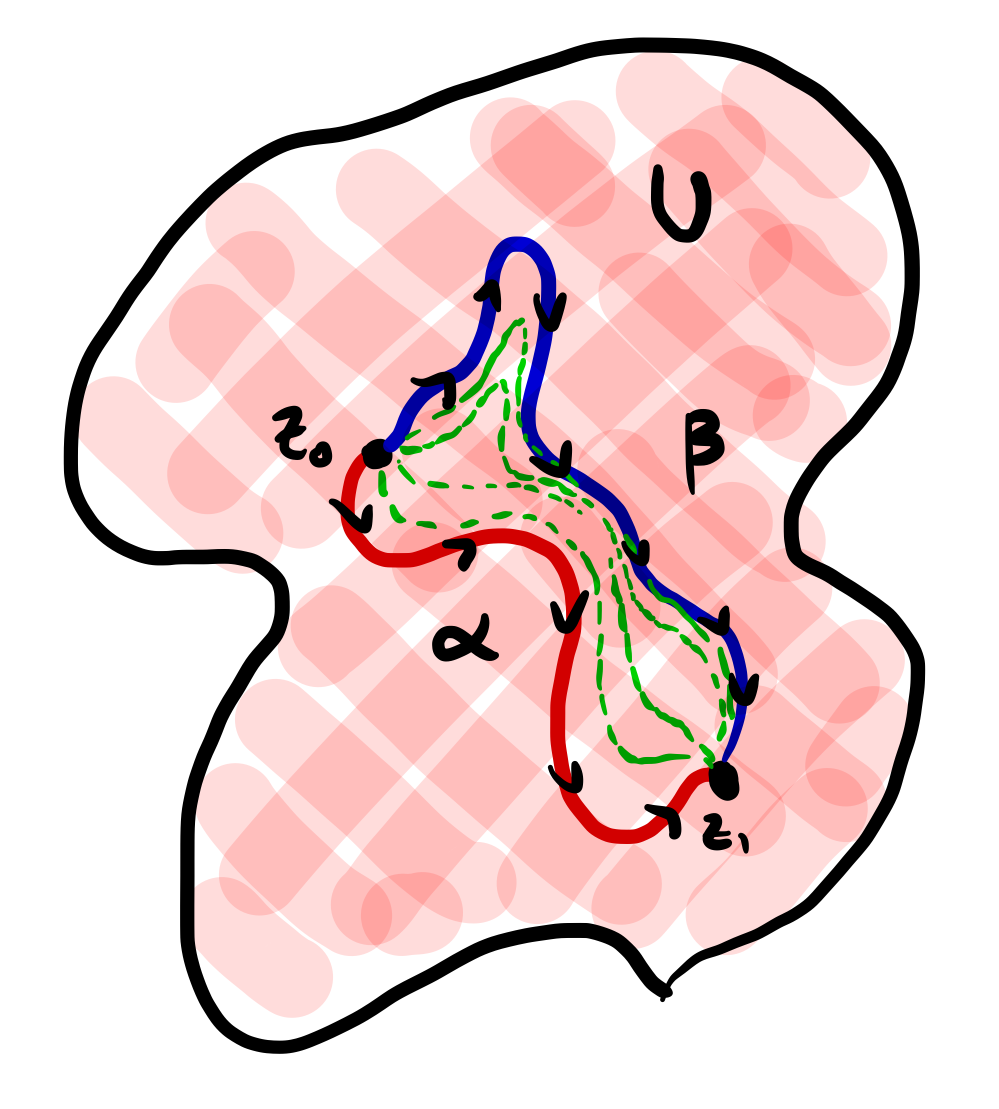

To this end note that for all \(z\in B_{\delta}(z_0)\text{,}\) we have

\begin{align*}

F(z)-F(z_0) \amp = \int_{z^*}^zf\, dz-\int_{z^*}^{z_0} f\, dz\\

\amp = \int_{z^*}^{z_0}f\, dz +\int_{\gamma_{z_0,z}}f\, dz-\int_{z^*}^{z_0}f\, dz\\

\amp = \int_{\gamma_{z_0,z}}f\, dz \text{,}

\end{align*}

where \(\gamma_{z0,z1}\) is the straight line path from \(z_0\) to \(z\text{.}\) Next, we have

\begin{align*}

\int_{\gamma_{z_0,z}}f\, dz \amp = \int_{\gamma_{z_0,z}}f(z_0)+f(z)-f(z_0)\, dz\\

\amp = \int_{\gamma_{z_0,z}}f(z_0)\, dz+\int_{\gamma_{z_0,z}}f(z)-f(z_0)\, dz\\

\amp =f(z_0)(z-z_0)+\int_{\gamma_{z_0,z}}f(z)-f(z_0)\, dz\text{,}

\end{align*}

where the last step follows from the fact that \(G(z)=z\) is an antiderivative of \(1\text{,}\) and thus

\begin{equation*}

\int_{\gamma_{z_0,z}}f(z_0)\, dz=f(z_0)\int_{\gamma_{z_0,z}}1\, dz=f(z_0)(z-z_0)\text{,}

\end{equation*}

by the fundamental theorem of calculus for line integrals.

Letting \(r(z)=\int_{z_0,z}f(z)-f(z_0)\, dz\text{,}\) we then have

\begin{equation*}

F(z)-F(z_0)=f(z_0)(z-z_0)+r(z)\text{.}

\end{equation*}

It remains to show that \(\lim\limits_{z\to z_0}\abs{r(z)}/{\abs{z-z_0}}=0\text{.}\) To this end, given any \(\epsilon > 0\text{,}\) shrink \(\delta\) as necessary so that \(\abs{z-z_0}< \delta\) implies \(\abs{f(z)-f(z)}< \epsilon\text{.}\) We then have

\begin{align*}

\frac{\abs{r(z)}}{\abs{z-z_0}} \amp = \frac{\abs{\int_{z_0,z}f\, dz}}{\abs{z-z_0}} \\

\amp \leq \frac{\epsilon \abs{z-z_0}}{\abs{z-z_0}} \amp (ML-\text{ineq.})\\

\amp \leq \epsilon\text{.}

\end{align*}

Since \(\epsilon\) was abribitrary, we see that \(\lim\limits_{z\to z_0}\abs{r(z)}/\abs{z-z_0}=0\text{,}\) as desired.